BOWERY

SYNAGOGUE

STUDIO

1958 — 1970

In 1958, Willard and his second wife, Susannah Kirkham Bond, moved into a huge loft on Manhattan's Lower East Side—245 Grand Street, at Bowery. The space was a decommissioned Orthodox synagogue, built in the 1860s, about 100 feet long, with a 30-foot high, pressed-tin ceiling, a large skylight, and ten stained-glass, arched windows along the side walls and across the back. At the front of the building facing the street, they discovered a large, stained-glass Rosetta window covered up by plywood and moved it up into the synagogue-loft space.

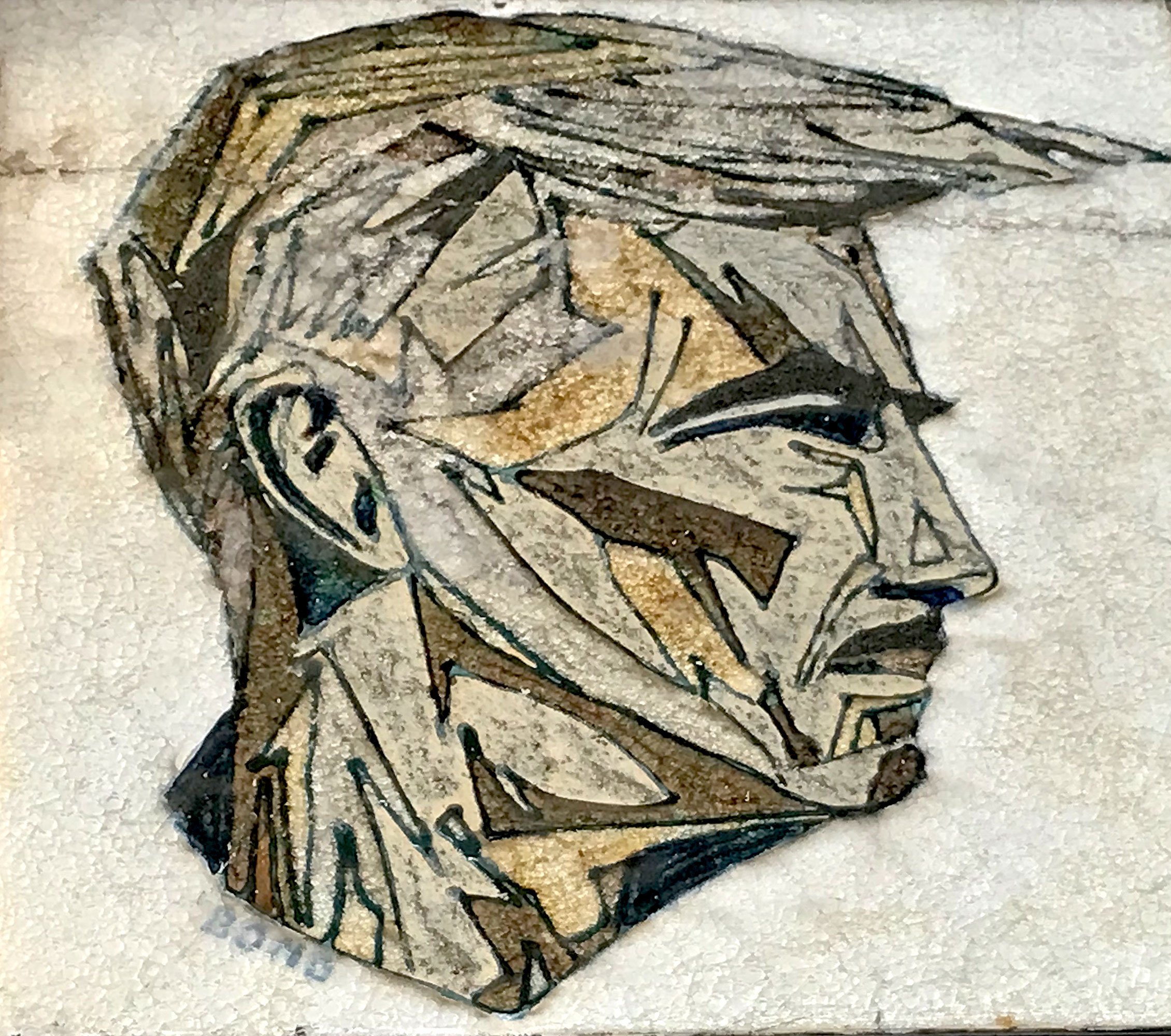

Click image to enlarge

They built living quarters in the front and an industrial-scale art studio in the back, with two ceramic kilns, large tables and painting easels. They hung a long swing from the high center beam below the skylight.

Over the next thirteen years, the place became known as a salon-style center of Bohemian life, with painting and ceramics, jazz and musical theater, dance, film, photography, and a revolving cast of friends and creatives in the arts community. Many of them were also from far away, each one drawn to New York, banding together with a common urge to find a new paradigm of living and creating; all seekers, all reinventing themselves

Click image to enlarge

Here, Willard and Susannah started a family, while she pursued her singing and acting career, and he had a productive decade of creating large-scale ceramic murals, Abstract and Expressionist paintings, theater sets and backdrops, and mid-century modern furniture and interiors. continued below

Click image to enlarge

IMMIGRANTS AND ARTISTS - WILLARD AND SUSANNAH BOND, LIVING IN THE BOWERY AND NEW YORK'S CULTURALLY RICH LOWER EAST SIDE

The synagogue building was owned in the 1950s and 60s by a very colorful Italian couple, Willy and Billie Ciccone, who owned a bridal gown shop at the street level. That whole block of Grand Street, between Bowery and Chrystie Street, had several bridal shops, with big plate glass windows. Once an Hasidic Jewish neighborhood, it was now an extension of Little Italy, just a block to the west, and was near the Orchard Street garment district. The old wholesale trade divisions of Manhattan were still active. There were industrial restaurant supply places around the corner along the Bowery, and lighting stores and furniture shops down Grand Street, filled with gawdy Italianate lamps and gilded furniture. The neighborhood had a community of several other artists who had inexpensive lofts and tenement apartments of various sizes and configurations. And of course, they all co-existed with the ever present "bums" who slept in the doorways and hung out at the Bowery missions, all men, mostly struggling with alcoholism.

On this corner of Grand and Bowery was Moishe's, a classic luncheonette establishment, with a long soda-counter and vinyl covered booths, where Moishe himself held court behind the cash register and where Willard bought his cigarettes. All the staff—who worked there for decades—knew the neighbors like family, serving up hamburgers, BLTs and NY egg creams.

In the front of the 245 Grand Street building, above the bridal store on the main floor and the synagogue on level two, were three additional floors, one with another artist studio space—originally a meeting room for the members of the synagogue—and the top two floors with regular, railroad-style apartments—original housing for the rabbi and family. In the 1960s, the Chang family lived in the first apartment, Ann and Jim Chang, immigrants from China, and their kids Perry and Cathy. The top apartment was where Margo and John Spoerri lived, both painters and art teachers, with their young kids, Stefan and Johanna. The synagogue itself, up a wide flight of stairs from the street to the building's second floor, stretched back into the quiet center of the block, and its roof, with the large skylight, was where the residents and friends got together for dinners and parties, often on hot, New York summer nights.

THE MAFIA CAME TO CALL

In 1966, Susannah and Gretchen moved back to the west coast, first to her family in Spokane then settling in Seattle. Willard remained in the synagogue until 1969, during which time he painted a series of luminous nudes from live models, built mid-century modern furniture and interiors, and was first the Lighting Manager and then became the Stage Manager for 300 shows of the original 1967 Off-Broadway musical, You're a Good Man, Charlie Brown.

One day, a few of the "boys" came up to see him. That was what the artists called the local, minor Mafiosos who played cards all day in a private club in the building next door, up in a small loft on the second floor. They always dressed in suits, looking pretty sharp.

That day, they buzzed the doorbell and Willard let them up, watching them slowly climb the main stairs to the synagogue's front door. They entered, looked all around and said, Will, you've got a pretty nice place here... and we're gonna trade with you. We're taking this place and you can rent our old card room next door. The synagogue's landlord was Italian–Willie Ciccone–and as Willard said, You don't argue with the Mafia. So, he lost his big studio, with all his equipment and art supplies, and many of the family's belongings–some of which went into storage but were never able to be retrieved.

ON TO NEW HORIZONS

Willard did move into the small loft next door, 243 Grand Street–which had the distinction of having a urinal in the bathroom–and added a shower and a hot plate. He lived there for about a year, while he worked as the Property Master on the 1970 (now cult) film Joe, staring Peter Boyle and Susan Sarandon in her first screen role. Then he gave up the Bowery life and happily moved "across the bridge" to Brooklyn Heights with his soon-to-be third wife, Lois Friedel. They remained together, off and on, for the next 40 years.

His next big adventure began when he and Lois moved to Jamaica together in 1971, where she taught in a primary school and he built several geodesic domes in the jungle.